File:Union Oil Spill On the Calif Coast - February 1969.png

Union_Oil_Spill_On_the_Calif_Coast_-_February_1969.png (640 × 351 pixels, file size: 371 KB, MIME type: image/png)

The 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill ranks as the third worst U.S. spill, with only the 2010 BP/ Deepwater Horizon Gulf of Mexico blowout, and the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil tanker spill off Alaska, ahead of it, ranking respectively as the nation’s No.1 and No. 2 spills.

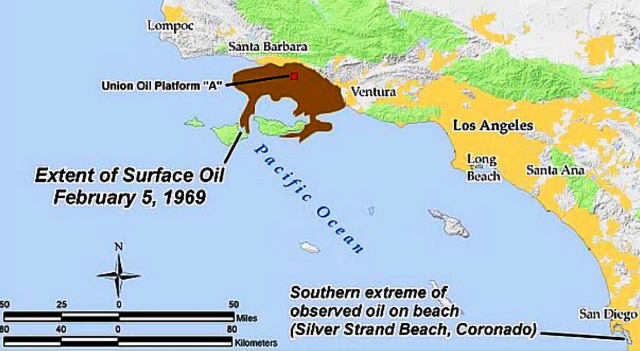

On January 28th, 1969, an oil well blow-out at Union Oil’s offshore platform in the Santa Barbara Channel six miles off the California coast, began one of the worst oil spills in U.S. history.

At one point, shortly after the blow out, a capping action at the well head on the platform appeared to have staunched the worst of the problem. However, complications down the well shaft due to insufficient well casings led to further problems: oil and gas escaped through the sides of the well bore and at several locations on the seabed floor below the rig. Nearby, on the water’s surface, oil and gas “boil ups” as they were called, could be seen, signaling the bigger problems below.

The worst of the spill would continue for 11 days, with lesser leaks continuing for months thereafter. Sea birds, seals, dolphins, kelp beds, and miles of beaches were coated with black crude. In the end, an estimated 80,000 to 100,000 barrels of oil were spilled and some 30-to-35 miles of California coastline tarred.

As the crude escaped during the blowout and from sub-surface releases it was spread over hundreds of square miles of open water by winds and swells. After a few days at sea, incoming tides brought the thick tar to beaches and towns along Santa Barbara County’s spectacular coastline, including: Goleta, home of University of California at Santa Barbara; the harbor at Santa Barbara; the coastline at Carpinteria; Rincon Point, the famous surfing beach; and Ventura. The farthest effects of the spill extended to Pismo Beach north of Santa Barbara, and south to the Silver Strand Beach at San Diego. Some beaches were spared the worst, as offshore kelp forests kept much of the crude from coming ashore. But a considerable length of California coastline, as well as coves and offshore islands, were hit by the spill. Frenchy’s Cove on Anacapa Island was hit, as well as beaches on Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, and San Miguel Islands.

“You go to the beach and you couldn’t hear the waves. All the ocean was black. People just stood their crying. We figured it was all over for Santa Barbara.” – Bud Bottoms, co-founder of Get Oil Out.

With the ’69 oil spill, people had this realization that we should protect the environment for the environment’s sake.

This concept of environmental rights emerged. UCSB history professor Rod Nash wrote this declaration of environmental rights and it was presented at this conference that was on the one year anniversary of the spill. He then went on to found the first environmental studies program in the U.S.

················································································································································

"How the First Earth Day Was Born from the 1960s Counterculture"

Via History.com

(First, a tip of the hat to the meaning of 'counterculture' / 'counter culture' via Wikipedia) - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Counterculture - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Making_of_a_Counter_Culture)

Growing Environmental Consciousness

Rachel Carson’s bestselling book Silent Spring, published in 1962, introduced many Americans to the devastating effects of the large-scale use of pesticides, especially DDT.

As the 1960s continued, more and more people became aware of other threats to the environment, such as automobile emissions, oil spills and industrial waste.

By 1967, the federal government had passed the first Clean Air Act, the first federal emissions standards and the first list of endangered species (including the bald eagle, America’s national symbol). These laws were a start, but they did not go far enough to address the serious environmental problems facing the nation.

In January 1969, the Union Oil well in Santa Barbara, California spilled more than 200,000 gallons of oil into the Pacific Ocean over 11 days. That June, oil and chemicals floating on the surface of the Cuyahoga River in Ohio burst into flames. Images of such disasters, broadcast across the country, helped fuel a growing outrage over the state of the environment, especially among young radicals.

Drawing Inspiration from the Anti-War Movement

Despite this growing consciousness, environmental activists hadn’t yet come together as a true movement by the end of the 1960s, as civil rights and anti-war activists had. This lack of momentum had long frustrated Gaylord Nelson, a Democratic senator and former governor of Wisconsin (1959-63) who was one of Congress’ most passionate environmentalists. During his years in the Senate, Nelson had also backed civil rights legislation and voted against appropriating funds for the war in Vietnam.

In August 1969, Nelson traveled to California, where he spoke at a water conference and visited the scene of the Santa Barbara oil spill. On that trip, he was struck by an article he read in Ramparts magazine about the anti-war “teach-ins” held on college campuses in the mid-1960s. Though teach-ins had been abandoned as an anti-war tactic, Nelson now saw their potential to energize people—especially young people—by educating them about the need to protect the environment.

On September 20, 1969, speaking at the annual symposium of the Washington Environmental Council in Seattle, Nelson announced that he was planning a nationwide teach-in on the environment for the following spring. “I am convinced that the same concern the youth of this nation took in changing this nation’s priorities on the war in Vietnam and on civil rights can be shown for the problem of the environment,” he said.

Grassroots Action and Bipartisan Backing

To put his plan into action, Nelson reached across the aisle in Congress, recruiting the Republican congressman Pete McCloskey of California to serve as his co-chair on the steering committee behind the event. Despite his otherwise conservative views, McCloskey was a committed environmentalist who also opposed the Vietnam War. In December 1969, Nelson hired Denis Hayes, the 25-year-old former president of the student body at Stanford University, as national coordinator of the Environmental Teach-In, as Earth Day was originally known. On a tight budget, Hayes recruited a small staff of volunteers, many of them students, to come to Washington, D.C. and coordinate Earth Day events in various regions of the country.

Thanks in large part to these committed young grassroots activists, the first Earth Day took place on April 22, 1970. In New York, 250,000 people flooded Fifth Avenue, after Mayor John Lindsay agreed to bar traffic for two hours between 14th and 59th Streets, all the way up to Central Park. In Miami, supporters of Eugene McCarthy, the anti-war presidential candidate in 1968, staged a parody of the Orange Bowl parade called the “Dead Orange Parade.” As Adam Rome recounted in his book The Genius of Earth Day, one of the parade’s floats featured the Statue of Liberty wearing a gas mask, standing on a pedestal made out of garbage.

··················································

Lasting Impact of Earth Day

Earth Day itself looks to origins in California, from student activists and members of the US Congress who joined to enlarge the message of a modern environmental movement that came out of a pro-peace movement of student teach-ins...

🌎

File history

Click on a date/time to view the file as it appeared at that time.

| Date/Time | Thumbnail | Dimensions | User | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| current | 12:52, 2 May 2023 |  | 640 × 351 (371 KB) | Siterunner (talk | contribs) |

You cannot overwrite this file.

File usage

The following 2 pages use this file:

- Anthropocene

- Atmospheric Science

- Biodiversity

- Biosphere

- Citizen Science

- Civil Rights

- Clean Air

- Clean Water

- Climate Change

- Earth

- Eco-ethics

- Eco-nomics

- Eco-Spirituality

- Earth Day

- EOS eco Operating System

- Earth360

- EarthPOV

- Earth Observations

- Earth Science

- Ecofeminism

- Ecology Studies

- Education

- Energy

- Environmental Laws

- Environmental Protection

- Environmental Security

- Environmental Security, National Security

- Food

- Global Security

- Global Warming

- Green Best Practices

- Green Networking

- GreenPolicy360

- Green Graphics

- Green Politics

- Health

- Human Rights

- Money in Politics

- Natural Resources

- Natural Rights

- Nature

- Networking

- New Definitions of National Security

- Overview Effect

- Peace

- Planet Citizen

- Planet Citizens

- Planet Scientist

- Planet Citizens, Planet Scientists

- Renewable Energy

- Resilience

- Seventh Generation Sustainability

- Solar Energy

- Strategic Demands

- Sustainability

- Sustainability Policies

- ThinBlueLayer

- US Environmental Protection Agency

- Water Quality

- Whole Earth

- Wildlife

- Women's Rights

- World Wide Web

- Youth