File:Usable climate science is adaptation science-Adam Sobel May 2021.jpg: Difference between revisions

Siterunner (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Siterunner (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

What to do | '''''What to do''''' | ||

'' | ''For many of us... there would be value in a more conscious, examined, and self-critical effort to develop a “theory of change” that explains the mechanism by which our research offers value to society.... reflective about the ways in which our work engages with the rest of society, or does not... We might cast a similarly critical gaze towards what becomes of the knowledge we generate once it leaves our laboratories and offices. These two sets of concerns are not just analogous, but intersecting as well, since what science is done is related to who does it and how.... (in this way) we might increase our contribution to societal welfare.....'' | ||

Revision as of 16:42, 11 May 2021

Usable climate science is adaptation science

By Adam H. Sobel | 20 April 2021/

Author has shared article for public reading with non-commercial usage

Visit Springer Nature B.V. for Full Article

{excerpts}

Introduction: The question I ask here to what extent, and for what purposes, climate science is usable.

If we scientists wish to understand what value our work brings to the larger world... (then) thinking through our work’s direct, near-term societal consequences is a good place to start. Physical scientists are not well trained to do this kind of thinking, but the increasing urgency of the climate problem drives some of us to try. Our colleagues in the history, philosophy, and sociology of science are, on the other hand, trained to think about these kinds of problems. At the same time, they do not personally face the choice of what kind of climate science to do (or, to take it further, whether to continue doing it at all). This essay expresses one climate scientist’s attempt to put more conscious effort into thinking about how our work engages with the broader society, learning from the social scientists and humanists who focus on this problem from the outside, but not leaving the task of understanding it entirely to them.

My primary claim is that at the present historical moment, climate science is only usable to the extent that it is oriented towards climate adaptation, rather than towards climate mitigation.

For the sake of concreteness, consider climate science research that is oriented towards determining the earth’s climate sensitivity, the overall index that measures the magnitude of global mean surface warming for a given increase in greenhouse gas concentrations.4 In fact, a large fraction of all research aimed at the basic physical, chemical, and biological processes of long-term climate change fits here, in that its claim to societal value rests, directly or indirectly, on its relevance to climate sensitivity. The earth’s climate sensitivity has remained stubbornly uncertain over half a century of study. Knowledge of climate sensitivity is relevant, broadly, to climate adaptation, in that it controls the overall extent of climate change, and thus of many socio-economic impacts to which adaptation is necessary (e.g., Seneviratne et al. 2016; Arnell et al. 2019), for a given increase in greenhouse gas concentrations. Arguments have also been made, however, that it is important to reduce this uncertainty in order to provide better guidance to climate mitigation policy. Several studies, in fact, explicitly justify it as being economically valuable on this basis, as discussed further below (Cooke et al. 2014; Hope 2015; Mori and Shiogama 2018). I argue here that such arguments are wrong, because they ignore political reality, and that better knowledge of climate sensitivity is only presently usable inasmuch as it may inform climate adaptation.

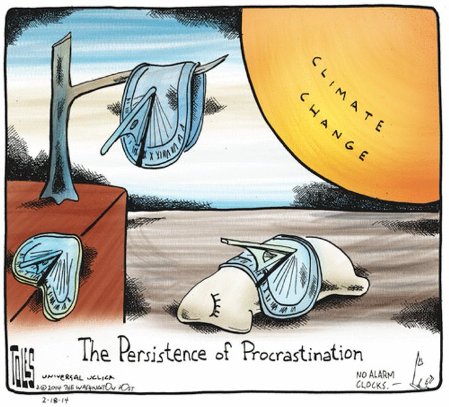

To achieve even a modest probability of averting dangerous climate change — we can use either 1.5 or 2 C average global surface warming compared to pre-industrial, those being the two targets most in use — dramatic reductions are needed in greenhouse gas emissions. Here “dramatic” can be quantified by recent IPCC reports, e.g., IPCC (2018), from which we obtain Fig. 1. Just a simple visual impression of the figure, noting the sharp change in slope between the historical emissions and the future emissions required to stay under 1.5C, gives a clear indication that a sharp discontinuity between recent past and near future emissions is necessary. (A 2C threshold would change the image quantitatively but not qualitatively, in that unprecedentedly dramatic emissions reductions would still be required to reach it. So the use of the 1.5C threshold, though central to IPCC (2018)... is not consequential to the argument here.). Results such as these underlie the commonly heard statements — accepted here as true — that “time is running out.”

No emissions reductions are planned that come anywhere near those necessary to stay under either a1.5 or a 2C target. Decades of international negotiations have, by any reasonable account, been a failure. And for the four years leading up to the most recent Presidential election, national policy in the USA in particular moved in the opposite direction.

New research is very unlikely to change the situation. The results in Fig. 1 come from a particular model with a particular climate sensitivity, but the broad conclusion of interest here is robust to plausible variations in that quantity (Rogelj et al. 2018; Forster et al. 2018). A new assessment, in fact, does argue persuasively for a significant reduction in the uncertainty range for Earth’s climate sensitivity, excluding the lowest and highest values previously considered possible (Sherwood et al. 2020). This is a truly important scientific achievement. Nonetheless, it is difficult to see how it will lead to major changes in climate mitigation policy, given the historical evidence that there is little coupling between the scientific evidence and greenhouse gas emissions. Whatever the source of any expectations that there should be such coupling may have been in the past, such expectations can now be understood to be naïve about the role of politics, and the power of entrenched interests to inhibit climate action...

○

What should climate scientists do to make a positive difference in the escalating #climatecrisis

Quotations from "Usable climate science is adaptation science"

by Adam Sobel

May 2021

Adam Sobel is a professor at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and Engineering School. He studies the dynamics of climate and weather phenomena, particularly in the tropics. In recent years he has become particularly interested in understanding the risks to human society from extreme weather events and climate change.

·······················································································

The only climate science that is truly usable is that which is oriented towards adaptation, because current policies and politics are so far from what would be needed to avert dangerous climate change that scientific uncertainty is not a limiting factor on mitigation.

The author considers what implications this might have for climate science and climate scientists....

The question I ask here to what extent, and for what purposes, climate science is usable. I define “climate science” for this purpose as science whose intent is to understand the climate system. Without trying to draw too precise a boundary around the set of people to whom my arguments (and my use of the pronoun “we”) apply, I certainly intend it to include those like me: scientists who study the mechanisms at work in the atmosphere and oceans, with some orientation towards the global scale, and who, if we were to participate in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), would be in Working Group I, which addresses the “physical science of climate change,” rather than societal impacts, adaptation, or vulnerability (Working Group II) or mitigation (Working Group III). I define “usable science” as science oriented towards decision-making....

Some of us (involved in climate science work) may wish to maximize — or at least increase — the contributions our research makes to the improvement of societal welfare, as some philanthropists wish to maximize the impacts of their financial contributions to saving or improving human life (e.g., Singer 2015). I take as axiomatic that usability, in the sense defined above (and discussed throughout this volume), measures the degree to which a given piece of climate science2 contributes to societal welfare in a direct, causally discernable way....

The full value of a piece of science, like that of a political action, cannot be fully measured in the moment, but may become clear only in a longer historical view....

My primary claim is that at the present historical moment, climate science is only usable to the extent that it is oriented towards climate adaptation, rather than towards climate mitigation. For the sake of concreteness, consider climate science research that is oriented towards determining the earth’s climate sensitivity, the overall index that measures the magnitude of global mean surface warming for a given increase in greenhouse gas concentrations.4 In fact, a large fraction of all research aimed at the basic physical, chemical, and biological processes of long-term climate change fits here, in that its claim to societal value rests, directly or indirectly, on its relevance to climate sensitivity....

To achieve even a modest probability of averting dangerous climate change — we can use either 1.5 or 2 C average global surface warming compared to pre-industrial, those being the two targets most in use — dramatic reductions are needed in greenhouse gas emissions. Here “dramatic” can be quantified by recent IPCC reports, e.g., IPCC (2018), from which we obtain Fig. 1. Just a simple visual impression of the figure, noting the sharp change in slope between the historical emissions and the future emissions required to stay under 1.5C, gives a clear indication that a sharp discontinuity between recent past and near future emissions is necessary. (A 2C threshold would change the image quantitatively but not qualitatively, in that unprecedentedly dramatic emissions reductions would still be required to reach it. So the use of the 1.5C threshold, though central to IPCC (2018), from which Fig. 1 is taken, is not consequential to the argument here.). Results such as these underlie the commonly heard statements — accepted here as true — that “time is running out.” No emissions reductions are planned that come anywhere near those necessary to stay under either a1.5 or a 2C target. Decades of international negotiations have, by any reasonable account, been a failure. And for the four years leading up to the most recent Presidential election, national policy in the USA in particular moved in the opposite direction. New research is very unlikely to change the situation....

Some history -- (t)here was a broad expectation — justified by the burst of environmental legislation and institution building in the 1970s and 1980s, including the signing of the Montreal Protocol and the formation of the IPCC — that advances in scientific understanding would influence policy in a relatively straightforward and nonpartisan way.

The consensus has eroded since the 1970s, and the role of scientific expertise in policy has been increasingly contested (e.g., Bocking 2004; Eyal 2019). To some extent this is for good reasons, well known to historians, philosophers, and sociologists of science: most environmental problems are not purely scientific, but rather “trans-scientific” problems (Weinberg 1972) in which critical uncertainties cannot be eliminated; values, as well as facts, are at issue; and democratic principles argue against leaving important decisions purely in the hands of technocratic experts. In addition, the public debate on multiple environmental and public health problems has — perhaps, again, especially in the USA — been plagued by bad-faith campaigns on the part of interested industry groups who cast doubt on the science as a conscious tactic to divert debate from the policy questions it raises (Oreskes and Conway 2010).

See Merchant's of Doubt by Naomi Oreskes & Erik M. Conway

In the context of repeated failures of the UNFCCC negotiations and the increasing influence of climate denial in US (and to some extent Anglophone world) politics, Howe (2014) describes the interaction between climate scientists and policymakers since the mid twentieth century as a tragedy, in the classical sense: the scientists’ words and actions repeatedly failed to achieve the results they expected, due to forces beyond both the scientists’ control and, to some extent, their comprehension. It is clear today that the climate mitigation problem is a political one, meaning that it will be solved only by changes in leadership, and beyond that, in the relative and absolute power held by relevant interest groups — especially, but not only, the fossil fuel industry (Oreskes and Conway). It will not be solved by advances in climate science, both because existing science is already adequate to justify more action than seems likely, and because the actions under consideration by current (and likely future) political actors are guided by science only, at best, in the loosest way.

To say that climate mitigation is currently a political rather than a scientific problem may seem obvious. It is certainly not a new statement (e.g., Sarewitz 2010). Does anyone disagree? Do any climate scientists really believe that, by doing research on the equilibrium climate sensitivity (for example) we are contributing to the solution of the climate problem in any direct way? I believe the answer is yes — or at least, that we often act, speak, and write as if it were. The simplest view of the interaction between science and policy is one in which science produces objective, “policy neutral” information that is nonetheless “policy relevant,” decision-makers adopt it, and better policies result. This has been called the “linear model”....

The linear model has been widely discredited. Its view of science as pure, apolitical, and value-free is naïve, and its view of expertise as directly constraining policy is in conflict with democracy (Jasanoff and Wynne 1998; Beck 2011; Durrant 2015). It encourages a scientism in which political disputes are recast as scientific ones, to the detriment of both science and policy (Pielke Jr 2007)... (Yet the linear model) discredited though it is (continues on as some scientists and others) posit a decision-maker who makes an optimal decision about emissions reduction given quantitative, global metrics of the costs of those reductions and the benefit of the reductions in global warming they would achieve. The decision-maker is assumed to be guided by the best available science on climate sensitivity and its uncertainty range, such that reductions in that uncertainty lead to improvements in the benefit/cost ratio. This decision-maker does not resemble any individual government that currently exists, let alone the collective action of the collection of governments in the world today.

Consider, then, the IPCC itself. On its front web page (ipcc.ch), the IPCC states its mission in large, bold font: “The IPCC was created to provide policymakers with regular scientific assessments on climate change, its implications and potential future risks, as well as to put forward adaptation and mitigation options.” And in somewhat smaller type, but still on the front page: “IPCC reports are neutral, policy-relevant but not policy-prescriptive.” What are these statements if not expositions of the linear model?

Perhaps the IPCC could not have formulated its mission differently. It was created to support an international negotiation process (with decisions necessarily left to the politicians), and in that, it can be argued that it has largely succeeded even if the negotiations have not. But as highly visible, even canonical documents of climate science — and ones which, in practice, strongly influence the direction of much climate research — IPCC reports define the stance of climate science and climate scientists as much as any single thing does.

Mitigation vs. adaptation

Mitigation is a global problem. Carbon dioxide and most other important anthropogenic greenhouse gases are long-lived and well-mixed, so that emissions anywhere are the same as emissions anywhere else as far as the atmosphere is concerned. The causal links between the emissions and the harms they cause are extremely nonlocal and diffuse compared to those with other pollution problems. The problem can only be adequately addressed by national governments; the actions of smaller units, such as individual US states, or even individual people, are important in the present political context, but will not be adequate unless they lead to larger scale action. My argument here is that there is no productive avenue by which further advances in climate science can be incorporated in a dialog with those governments so as to influence mitigation policy in a pragmatic way — at least, not until the governments, particularly in the USA but not only there — change very substantially, and perhaps not even then.

Adaptation, on the other hand, is local; unlike mitigation, it is different everywhere.6 There may be commonalities, potential for shared learning, and so on, but the nature of climate hazards varies greatly across the planet, as do the ways in which the hazard interacts with social, economic, political, and cultural factors to generate the risks that adaptation aims to address. The users, or “stakeholders,” need not be national governments; they need not be governments at all. Thus, they are a much more diverse set of actors than those who have major roles in mitigation, and this diversity creates many more opportunities to do scientific research in support of adaptation.

The existence of opportunities to do climate science for adaptation does not imply that doing such science is straightforward, however, or that physical scientists’ typical training is adequate preparation for it. Adaptation is a human activity, and just as with mitigation (if perhaps in different ways) science is just one consideration relevant to it, alongside social, cultural, economic, and political factors. One needs to learn how to do such work and to consider for whom one is doing it, why, and whether it will be effective. Success requires that scientists engage in “co-production7” of usable science with stakeholders, and that they do so with humility and willingness to learn to understand how the human factors are manifest in any particular setting. Engagement of this kind is fundamental to organizations engaged in climate services, including the International Research Institute for Climate and Society, Future Earth, and the American Geophysical Union’s Thriving Earth Exchange. Barry (2020, this volume) describes a “community science” model for doing “place-based research centered on the concerns and goals of local residents....”

What to do

For many of us... there would be value in a more conscious, examined, and self-critical effort to develop a “theory of change” that explains the mechanism by which our research offers value to society.... reflective about the ways in which our work engages with the rest of society, or does not... We might cast a similarly critical gaze towards what becomes of the knowledge we generate once it leaves our laboratories and offices. These two sets of concerns are not just analogous, but intersecting as well, since what science is done is related to who does it and how.... (in this way) we might increase our contribution to societal welfare.....

○

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

"Thin Blue", Protecting 'The Commons', Enabling Life on Earth

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

○

File history

Click on a date/time to view the file as it appeared at that time.

| Date/Time | Thumbnail | Dimensions | User | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| current | 22:24, 10 May 2021 |  | 702 × 664 (155 KB) | Siterunner (talk | contribs) |

You cannot overwrite this file.

File usage

There are no pages that use this file.

- Air Quality

- Air Pollution

- Agriculture

- Alternative Agriculture

- Antarctica

- Anthropocene

- Arctic

- Atmospheric Science

- Citizen Science

- City Governments

- Climate Change

- Climate Migration

- Climate Policy

- County Governments

- Desertification

- Digital Citizen

- Earth Imaging

- Earth Observations

- Earth360

- Earth Science

- Earth Science from Space

- Earth System Science

- Ecology Studies

- Eco-nomics

- Economic Justice

- Education

- Energy

- Environmental Laws

- Environmental Protection

- Environmental Security

- Environmental Security, National Security

- ESA

- European Union

- Externalities

- Extinction

- Florida

- Food

- Forests

- Fossil Fuels

- Greenland

- Global Security

- Global Warming

- Green Networking

- Green Best Practices

- Green Graphics

- Green Politics

- Health

- INDC

- Maps

- Money in Politics

- NASA

- NOAA

- Natural Resources

- Networking

- New Definitions of National Security

- New Economy

- New Space

- Oceans

- Ocean Science

- Online Education

- Planet Citizen

- Planet Citizens

- Planet Citizens, Planet Scientists

- Rainforest

- Renewable Energy

- Resilience

- Sea-level Rise

- Sea-Level Rise & Mitigation

- Seventh Generation Sustainability

- Social Justice

- Soil

- Solar Energy

- Strategic Demands

- Sustainability Policies

- Threat Multiplier

- United Nations

- US

- US Environmental Protection Agency

- Water Quality

- Whole Earth

- Wind Energy

- World Bank

- World Wide Web

- Youth