Category:Democratization of Space

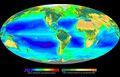

Democratizing Earth Science & Earth Observation

Earth Science Research from Space

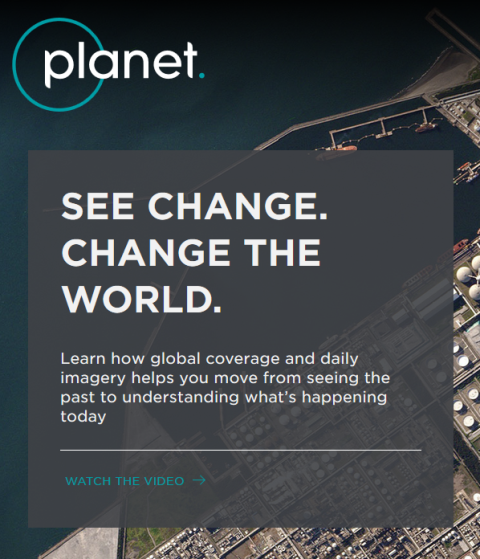

Announcement / Planet Labs is now just 'Planet'

NASA Democratizing Space Research With Android / 2012

Planet Labs & NASA

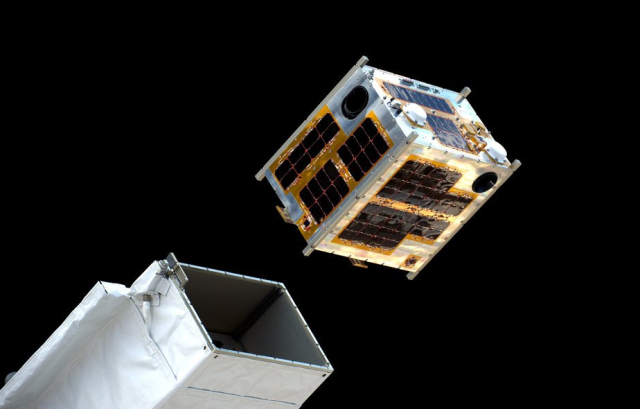

Built and operated by Planet Labs of San Francisco, the Flock 1 small satellites are individually referred to as Doves. The Dove satellites are part of a class of miniature satellites often called CubeSats. These small satellites will capture imagery of Earth for use in humanitarian, environmental and commercial applications. Data collected by the Flock 1 constellation will be universally accessible to anyone who wishes to use it.

“We believe that the democratization of information about a changing planet is the mission that we are focused on, and that, in and of itself, is going to be quite valuable for the planet,” says Robbie Schingler, co-founder of Planet Labs. “One tenet that we have is to make sure that we produce more value than we actually capture, so we have an open principle within the company with respect to anyone getting access to the data.”

CubeSats like the Doves in the Flock 1 constellation are just the tip of the iceberg. As new CubeSats deploy, more data is gathered, systems are optimized and, eventually, new types of spacecraft are developed based on their predecessors in space. The space station allows for the expansion of commercial ventures in low-Earth orbit. The Earth-imaging mission of Planet Labs’ Flock 1 takes another leap toward creating benefits on Earth resulting from innovation in space.

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

Q & A -- Forbes & Planet Labs / 2014

Planet Labs is a San Francisco-based startup that is using the world’s largest fleet of imaging satellites to continuously monitor Earth. The three founders are physicists who previously worked at NASA, and founded Planet Labs to provide universal access to information about the changing planet.

Give us a high-level overview of what Planet Labs is working on...

Will: We’re launching a large number of ultra-compact satellites so we can image the earth on a much more frequent basis. This is something that’s never been possible before. We believe that there is tremendous humanitarian and commercial value from that data and we care about pursuing both. We launched four demo satellites last year on three different launch vehicles testing our technology and this year we just launched our first fleet of 28 satellites. This is already the largest constellation of earth imaging satellites in human history and it’s going to be producing an unprecedented data circuit that enables us to image the whole earth on a much more rapid basis than has ever been possible before...

We’re imaging the whole earth on a regular basis.

How does the Planet Labs team balance humanitarian goals with commercial viability?

Robbie: We plan to offer a tiered pricing system as well as a freemium model. If you are a small farmer in Mozambique and you’re only looking at a hectare of data, take it. If you are a commodity trader looking at the Kenyan crop and you’re looking at millions of hectares, we have a different pricing structure. This allows us to ensure the democratization of data...

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

Tech Beyond Science Fiction / 2012

There’s real movement behind the democratization of space. Not in the form of sending more people into space, but in giving more people access to satellites. Nano-satellites are getting cheap enough now that groups can raise enough money on Kickstarter to buy and launch them... If there’s any sort of democratization of space, it’s some sort of cheap space travel. Satellites don’t get much attention. The idea of everyone being able to rent time on a satellite seems truly novel. The fact that, even though I probably never will, I could learn to write apps for satellites and actually pay to have them run on a real satellite in space is much more amazing to me than being able to tell my phone to book an appointment on my calendar.

Although Android phones and Arduino boards are newish, and the cost of electronics has gone down, I don’t see a big reason why some sort of citizen satellites wouldn’t have been possible years ago. What it really took was a small leap of imagination, and that’s something I don’t take for granted anymore."

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

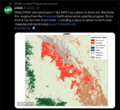

The Disruptive Democratization of Space: Tiny satellites are diffusing remote sensing capabilities around the world / 2014

In the last seven years, twenty-one countries, never before in space, have launched small satellites. Several US states have launched their own satellites, and Alaska even has its own state-owned launch complex. In the last two years, five private companies have formed to launch small satellites... These tiny satellites-on-demand are a brilliantly disruptive application of an old technology, and established players often do not readily spot truly disruptive change. For some time, big has been a big cultural issue in the US space enterprise, as solutions are often sized for existing infrastructure. The US government and US industry need to be aware of what is becoming possible at tiers below their usual product categories.

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

The US Foreign Policy Establishment Looks at the Democratizing of Space / 2015

In 1967, the United States, the Soviet Union, and many other countries signed the Outer Space Treaty, which set up a framework for managing activities in space—usually defined as beginning 62 miles above sea level. The treaty established national governments as the parties responsible for governing space, a principle that remains in place today.

Half a century later, however, building a basic satellite is no longer considered rocket science. Thanks to the availability of small, energy-efficient computers, innovative manufacturing processes, and new business models for launching rockets, it has become easier than ever to launch a space mission. These advances have opened up space to a crowd of new actors, from developing countries to small start-ups. In other words, a new space race has begun, and in this one, nation-states are not the only participants. Unlike in the first space race, the challenge in this one will not be technical; it will be figuring out how to regulate this welter of new activity.

FREE-FOR-ALL

Computing gets much of the credit for lowering the barriers to entry to space. The modern smartphone is the product of three-plus decades of advances in circuit design and fabrication techniques, and today’s processors pack 1,000 times as many transistors as their predecessors did 20 years ago. The iPhone 6 has as much computational power as a supercomputer from the 1990s did. Smaller also means more energy efficient: a typical cell phone will draw just 25 cents’ worth of electricity in a year, compared with the $36 worth a typical desktop computer does. Small, powerful, and energy-efficient hardware is perfectly suited for satellites, which have a finite amount of electricity (from solar panels) and volume. And thanks to new software-development tools and customizable hardware, anyone with even a modest programming ability can assemble a highly capable computer that could fit into a satellite.

TIME TO PLAN

The democratization of space will pose new challenges for policymakers, given that for the most part the existing legal framework has effectively applied to only a handful of states...

THE NEW SPACE RACE

Given the abundance of challenges, policymakers will have to resort to triage. Some problems are overdue for a solution, others are imminent, and still others are merely emerging... The space community now finds itself in the same position that software developers did at the beginning of the smartphone age: an exciting new platform is about to open up, but governments have barely started to plan for how it will be used.

○

SpaceX, NASA & Beginnings of 'New Space'

The first successful flight of the Falcon 1 (in 2008) served as a catalyst for the commercial space industry. The privately financed development of new rockets and spacecraft, as well as commercial businesses in space beyond telecommunications, had seen ups and downs over the years but never sustained success. SpaceX’s second successful launch of the Falcon 1 rocket in 2009, when it delivered a commercial satellite into orbit, sealed the deal.

“The impact that their first successful commercial launch had on the space industry cannot be overstated,” said Chad Anderson, who runs an investment group, Space Angels, that closely tracks public and private investment in spaceflight.

This initial success helped land a multibillion dollar contract from NASA to deliver cargo to the space station and ignited a furious decade in which SpaceX has gone from a single engine rocket, to one with nine engines, to one with 27 engines. The company has also developed two spacecraft, the Dragon 1 and 2, and landed dozens of first stages.

Before SpaceX began flying the Falcon 1 rocket, there were a few dozen privately funded companies, globally, engaged in spaceflight activities. Today (as of 2018), there are 350, and they have raised $15 billion in private capital...

○

Subcategories

This category has the following 5 subcategories, out of 5 total.

E

G

N

P

Pages in category "Democratization of Space"

The following 48 pages are in this category, out of 48 total.

C

D

E

G

- Generation Green

- Global Fishing Watch

- Global Forest Watch

- Global Risks Report

- Going Green: Texas v. Pennsylvania

- GP360 NewPages

- Green Bank in Maryland - and More

- Green Stories of the Day

- Green Stories of the Day - GreenPolicy360 Archive

- GreenPolicy360 Archive Highlights 2013

- GreenPolicy360 Archive Highlights 2014

- GreenPolicy360 Archive Highlights 2015

- GreenPolicy360 Archive Highlights 2016

- GreenPolicy360 Archive Highlights 2017

- GreenPolicy360 Archive Highlights 2018

- GreenPolicy360 Archive Highlights 2019

- GreenPolicy360 Archive Highlights 2020

- GreenPolicy360 Archive Highlights 2023

- GreenPolicy360 Highlights

P

Media in category "Democratization of Space"

The following 200 files are in this category, out of 294 total.

(previous page) (next page)- A Flash of Green by John D. MacDonald.jpg 400 × 400; 55 KB

- A Planet Citizen View.png 799 × 1,241; 1.64 MB

- A View of the Earth and Moon from Mars.jpg 720 × 890; 3 KB

- All Alone In the Night.png 831 × 426; 275 KB

- Anti science, anti open data - EPA April 2017.png 429 × 616; 198 KB

- API connect.jpg 490 × 120; 22 KB

- As Earth Warms, NASA Targets 'Other Half' of Carbon, Climate Equation.jpg 1,504 × 846; 242 KB

- Astro POV - Mike Massimino - PlanetCitizen.png 800 × 466; 792 KB

- Astro Sam w new espresso machine's first cuppa java May2015.png 585 × 377; 375 KB

- Astro Samantha.png 448 × 266; 78 KB

- Aurora from the ISS 2016.png 844 × 434; 150 KB

- Away fly the Doves March4,2015.png 582 × 409; 167 KB

- Backbone of Night - The Milky Way by Andrew McCarthy 2023.png 796 × 1,722; 2.3 MB

- Battle for Democracy.jpg 640 × 123; 24 KB

- Be a planet citizen, make a choice, act to reduce climate change.jpg 1,024 × 595; 60 KB

- Be Worried, Be Very Worried.jpg 400 × 533; 211 KB

- Ben Santer to Pruitt March 2017.png 506 × 420; 0 bytes

- Biden-Harris, CNN News Online - Nov 8, 2020.jpg 800 × 484; 114 KB

- Biden-January 27 2021-Environment Day 1-News headlines.jpg 800 × 673; 122 KB

- Biden-January 27 2021-Environment Day 1.jpg 800 × 500; 80 KB

- Blue atmosphere from Astro Wheelock.jpg 800 × 532; 16 KB

- Blue fragile edge thin blue line.jpg 1,200 × 798; 26 KB

- Blue Marble photo - Apollo 17.jpg 642 × 605; 129 KB

- Blue Marble photo taken by the crew of Apollo 17 (1972).jpg 642 × 605; 129 KB

- Blue Marble updated-August 2015.jpg 1,024 × 341; 109 KB

- Brief History of Carbon Emissions as of 2016.png 770 × 425; 342 KB

- CAIT Map 1.png 800 × 415; 123 KB

- Carbon Mapper - Launch - April 2021.jpg 800 × 323; 92 KB

- Cardinal directions m.png 250 × 250; 20 KB

- Celebrating 50 Years of Landsat.png 600 × 610; 909 KB

- Christina Korp Earth Day and Apollo 8.jpg 519 × 264; 80 KB

- Citizens Climate Lobby - Save Our Future Act 2021.jpg 518 × 262; 77 KB

- Climate cases on the rise - Nature, Sept 2021.png 800 × 562; 181 KB

- Climate Change from Space - Climate Kit via ESA - 2022.png 800 × 421; 651 KB

- Climate Change Laws - database collaboration.png 640 × 271; 76 KB

- Climate Change Laws of the World - database.PNG 768 × 845; 383 KB

- Climate Change Litigation Databases Climate Law.png 800 × 330; 73 KB

- Congressman george.e.brown.gif 235 × 305; 41 KB

- Crew-1 over New Zealand.jpg 570 × 523; 86 KB

- CSDA Program and Planet.jpg 800 × 379; 99 KB

- Cube Launch from the ISS via Tim Peake.png 640 × 409; 218 KB

- Dawn above Earth-May 2018-AstroPOV.png 640 × 712; 204 KB

- Democratization of space Google June 2015.png 565 × 716; 114 KB

- Dove minisat launch from ISS m.png 800 × 526; 528 KB

- Dove minisat m.jpg 613 × 298; 42 KB

- Dove1 image.jpg 420 × 308; 26 KB

- Doves fly 2016.jpg 800 × 533; 89 KB

- Doves fly from the ISS March03,2015.png 985 × 656; 0 bytes

- Doves launched from ISS float against Earth horizon m.jpg 807 × 537; 52 KB

- Doves launched from ISS float against Earth horizon s.jpg 553 × 368; 35 KB

- Doves launched from ISS float against Earth horizon.jpg 4,256 × 2,832; 564 KB

- DSCOVR looks back at earth from a million miles away m.jpg 1,004 × 469; 40 KB

- DSCOVR looks back at earth from a million miles away.jpg 1,446 × 670; 65 KB

- DSCOVR w EPICcam, PlasMag & NISTAR.png 1,219 × 785; 1.49 MB

- DSCOVR w EPICcam.png 800 × 515; 968 KB

- DSCOVR-EPIC 187 1003705 americas dxm.png 985 × 985; 1.21 MB

- DSCOVR-EPIC 187 1003705 m americas dxm.png 502 × 502; 330 KB

- DSCOVR-EPIC ImagingofPlanetEarth 2.png 686 × 628; 449 KB

- DSCOVR-EPIC ImagingofPlanetEarth.png 316 × 266; 19 KB

- DSCOVR-EPIC-May13,2018.png 760 × 872; 598 KB

- Earth 3D Overview.jpg 1,024 × 768; 190 KB

- Earth and atmosphere from Suomi.jpg 1,484 × 1,113; 349 KB

- Earth and Space, Politics.png 796 × 765; 349 KB

- Earth at the Tipping Point April 2006 Time.png 711 × 330; 251 KB

- Earth atmosphere and night-1920x1080.jpg 1,920 × 1,080; 390 KB

- Earth atmosphere ISS October30,2014.jpg 590 × 392; 12 KB

- Earth atmosphere.jpg 1,440 × 1,080; 153 KB

- Earth Day - DSCOVR-EPIC 2019.jpg 800 × 772; 150 KB

- Earth day 2016.jpg 704 × 220; 35 KB

- Earth Day 2022 - Act up.png 457 × 370; 155 KB

- Earth from DSCOVR.jpg 1,024 × 1,024; 156 KB

- Earth grassroots.jpg 374 × 238; 32 KB

- Earth imaging.jpg 620 × 465; 314 KB

- Earth Right Now science.jpg 197 × 49; 3 KB

- Earth Right Now.png 583 × 365; 145 KB

- Earth Science Vital Signs, Pulse of the Planet Climate Essentials.png 692 × 441; 207 KB

- Earth Science Vital Signs, Pulse of the Planet EOS NASA 2014.png 758 × 776; 366 KB

- Earth System Observatory.jpg 457 × 338; 47 KB

- Earth topo observatory nasa 1024x512.jpg 1,024 × 512; 96 KB

- Earth-BlueMarble-climate.gov .jpg 680 × 400; 114 KB

- EarthPOV 1920x1080.jpg 1,920 × 1,080; 270 KB

- Earthrise - NASA - Astro Bill Anders.png 497 × 479; 216 KB

- Earthrise2015 m.png 703 × 449; 346 KB

- Earthrise2015.png 1,004 × 642; 558 KB

- Earths Atmospheric Layers.JPG 800 × 532; 34 KB

- Earths rotation as we roll thru space.jpg 800 × 529; 69 KB

- Earths two lungs.png 336 × 336; 130 KB

- Earths-atmosphere-from-ISS.jpg 1,536 × 864; 114 KB

- EarthsAtmosphere 4628x1500.jpg 4,628 × 1,500; 1.45 MB

- Earthview ISS Shuttle.jpg 1,152 × 648; 0 bytes

- Earthview nasa date-unknown search1.jpg 768 × 432; 79 KB

- Education experiments going up on SpaceX.png 879 × 573; 450 KB

- Elon.jpg 300 × 168; 10 KB

- Environmental Security ThinBlueLayer.png 814 × 677; 469 KB

- EnvirSecurity.png 558 × 166; 155 KB

- EPA website - Climate Change priority - March 2021.jpg 786 × 600; 140 KB

- Epic 1b 20160615154340 01.jpg 2,048 × 2,048; 250 KB

- Epicday260.gif 985 × 554; 2.76 MB

- Evolution of Human Energy Use - 1800-2020.png 800 × 450; 199 KB

- Eyes On Global Security Threats - via Strategic Demands April 2022.png 600 × 776; 308 KB

- Fact Checking organizations at work.jpg 800 × 390; 44 KB

- Facts Count-WaPo Reports-19127 false-misleading claims in 1226 days.jpg 601 × 489; 100 KB

- Fallows re Brown speech to the AGU Dec2016.png 533 × 354; 65 KB

- Feeling the Heat 1989.png 800 × 1,095; 400 KB

- Florida Flyover.jpg 800 × 448; 51 KB

- From above m.png 752 × 318; 475 KB

- From above.png 1,274 × 539; 1.03 MB

- G7 Climate News.png 640 × 205; 125 KB

- G7 DJTclimatetweet.png 640 × 300; 45 KB

- G7 Split-2017.png 800 × 182; 177 KB

- G7-Climate-2017.png 800 × 136; 66 KB

- G7-Climate-News.png 640 × 317; 176 KB

- Gateway to Astronaut Photography of Earth.png 1,024 × 409; 731 KB

- Gavin in Glasgow - Nov 10 2021.png 728 × 600; 378 KB

- Gavin Schmidt - NASA - January 2022.png 451 × 436; 150 KB

- Geosciences satellite fields b.jpg 461 × 444; 186 KB

- Global Apollo Programme .png 654 × 156; 29 KB

- Global biosphere image NASA-Goddard.jpg 360 × 230; 36 KB

- Global CO2 Emissions 1900-2010.png 714 × 352; 15 KB

- Google Earth Engine.png 448 × 165; 45 KB

- Green dragon over Iceland 2015 Belegurshi.jpg 960 × 960; 57 KB

- Green Networking @GreenPolicy360.net.png 788 × 604; 764 KB

- Green Something to Think About.png 480 × 480; 200 KB

- Guarding Earths Water - from Space.jpg 578 × 496; 102 KB

- Hawaiian fires and climate.jpg 600 × 600; 128 KB

- High Seas Treaty agreement - March 4 2023.png 617 × 498; 53 KB

- Hottest decade on record.jpg 776 × 490; 69 KB

- How Earth Survived - Time Magazine - Sept 2019.jpg 644 × 858; 193 KB

- How thin is earth's atmosphere.jpg 605 × 292; 61 KB

- Human history, as an 800 page book.jpg 799 × 1,112; 148 KB

- IEA energy chart - 2023.jpg 600 × 600; 68 KB

- In Love with Earth.jpg 328 × 499; 15 KB

- ISS view 2016.png 800 × 400; 165 KB

- ISS025E006291viaDougWheelock.jpg 3,246 × 1,937; 715 KB

- Iss040e008179 earth's atmosphere .jpg 638 × 276; 19 KB

- Jerry Brown AGU-Dec14,2016.png 476 × 344; 117 KB

- Joe Biden is projected winner Nov7-2020.jpg 343 × 120; 26 KB

- Kidscelebrateclimatelawsuit.jpg 480 × 319; 52 KB

- Lamar-smith-press 2015.jpg 640 × 427; 49 KB

- Land Remote Sensing Policy Act of 1992.jpg 563 × 480; 144 KB

- Landsat at AT.png 762 × 598; 972 KB

- Landsat band imagery.png 800 × 400; 907 KB

- Landsat band imagery2.png 800 × 400; 907 KB

- Landsat data site.png 657 × 600; 499 KB

- Landsat Imaging the Past-1.png 767 × 744; 242 KB

- Landsat Imaging the Past-2.png 767 × 667; 329 KB

- Landsat Imaging the Past-3.png 767 × 560; 178 KB

- Landsat Imaging the Past-4.png 767 × 833; 496 KB

- Landsat Imaging the Past-5.png 767 × 870; 791 KB

- Landsat Imaging the Past-6.png 767 × 735; 385 KB

- Landsat launched 50 years ago today.png 528 × 779; 755 KB

- Landsat NASA - Feb 11 2023.png 763 × 600; 578 KB

- Landsat US collection of maps 1985-2021.png 768 × 775; 1,018 KB

- Landsat, a 50 year legacy.png 528 × 575; 288 KB

- Landsat-Google Maps Screen Shot 2016-06-17 Columbia Glacier.jpg 1,200 × 587; 312 KB

- Life on Exoplanets.jpg 591 × 523; 75 KB

- Map of the World wiki commons GTN800x370.png 800 × 370; 39 KB

- Mapping the Earth with Google Earth Outreach.jpg 640 × 648; 109 KB

- March for Science-1.png 800 × 291; 596 KB

- Michael Mann, planet citizen.png 604 × 835; 273 KB

- Michael Mann-Nov7,2018.png 676 × 796; 471 KB

- Milky Way Map.png 768 × 847; 1.04 MB

- Minerals used in clean energy technology - circa 2022.png 800 × 580; 197 KB

- Model 3 Elon TW.png 374 × 169; 39 KB

- Mysterious circles around the world.png 733 × 600; 655 KB

- NanoRacks.png 529 × 826; 72 KB

- NASA and micro nano sats.png 443 × 431; 43 KB

- NASA Earth - Identifying methane gas leaks - 2021.jpg 522 × 409; 67 KB

- NASA earth observation fleet as of April 2017.jpg 800 × 450; 184 KB

- NASA Earth science from space May2015.png 486 × 618; 260 KB

- NASA Gateway to Astronaut Photography of Earth.png 800 × 351; 485 KB

- NASA has a new mission... against Methane.png 800 × 576; 681 KB

- NASA MODIS One week in April 2016.jpg 800 × 480; 87 KB

- NASA-DSCOVR and GreenPolicy360-July2016.png 577 × 575; 96 KB

- NASAblog iss051e050137.jpg 800 × 450; 27 KB

- Navigate with Knowledge - StratDem - GreenPolicy360.jpg 800 × 534; 62 KB

- NOAA Earth Systems Labs.jpg 760 × 758; 115 KB

- Oh Aurora Borealis.gif 718 × 404; 29.36 MB

- Oh Aurora.gif 800 × 450; 4.67 MB

- On the road sjs.jpg 293 × 249; 0 bytes

- On-the-Road-11.jpg 800 × 326; 52 KB

- Over New Zealand - 2017.png 1,024 × 504; 995 KB

- Over Paris via StationCDR-ScottKelly Nov302015.png 885 × 473; 544 KB

- Over Planet Earth.png 800 × 490; 749 KB

- Over the Sahara 'how thin the atmosphere is' from Tim Peake.jpg 1,024 × 305; 35 KB

- Overview Effect by Frank White.jpg 470 × 716; 73 KB

- Overview planet earth1.jpg 640 × 272; 17 KB

- Pale Blue Dot - The Book by Carl Sagan 2.jpg 330 × 143; 17 KB

- Paris Climate Summit 195 Nations Challenged INDCs.png 512 × 127; 21 KB